| Side One: | Side Two: |

|

|

Thanks to the questionable choices of WordPress¹, I lost about two hours solid of writing on the initial draft of this, which left me irritated enough to just sit—writing irritated on something like this is a recipe for disaster.

Now, then.

It’s not for nothing that I restart a previously dormant project. I’ve been mostly running things (in an entirely different style) at Meandering Milieu, covering more in the range of comics and movies than anything else. Music never really stops being an important part of my world, but this particular blog (as I noted in my review of the previous album by Davenport Cabinet) is not really suited to writing during full-fledged employment, as it takes a pretty hefty time investment to do it the justice I intend.

Why, then, is it being revived?

Well, a few weeks ago I was at a show and met Travis Stever of Davenport Cabinet. After some jokes passed around the circle², I mentioned that I’d written the “vinyl” review of Our Machine and Mr. Stever very amicably told me he’d liked it and asked me to let him know what I thought of the new album. In my head, there was a twinge: I’d recently fallen out of favour with the employment gods, and had not pre-ordered the album as I’d hoped, but figured I’d just drop a line when I got around to it. I thought it was kind to respond with memory, but figured the chances that my one rambling writing had struck enough of a chord to stick were pretty low and let it be (and enjoyed the show).

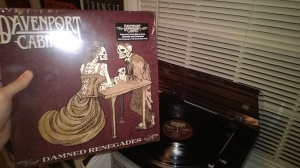

Turns out, I may’ve been mistaken, as I was prodded out of the blue with a very polite question about actually writing something on the new album—after a moment of stunned confusion and pancake-levels of flattery, I agreed and snagged a promotional copy. Turns out that, taking pity on my financial state, this particular album (in the ultra-fancy, all-the-bells-and-whistles bundle form) had been pre-ordered for me by my own mother (thanks, ma!), of which I was notified after I mentioned the shocking request. That, then, is how a not-vinyl promotional copy was reviewed on vinyl and photographed poorly above, should you be curious.

Now, I realize that with a context like this, it might seem as if I’ve either been buttered, or am aiming to do so myself. I can very, very strongly testify to the contrary: that two hours I lost was crushing. It takes a lot to put this particular approach together, and that informs, further, why it’s not at all fun to do for anything mediocre (or less!). Witha predecessor like Our Machine, though, it’s not a huge gamble–it was in my Top 5 for the year last year—vacillating between two and three because I’m indecisive. These things together meant I was confident that doing this would be worthwhile to myself, anyone reading, and the band in question, with no questions about ethics (barring those who just can’t resist)

It’s a set of coordinates on which we open the album: “41°15’22.0″ N”. Deep, warm tones are interrupted and subsumed by sharp, distinct, clean guitar and the long-drawn bows of E’lissa Jones’s violin and viola. It’s quiet and a bit sad, the guitars acting to counter the other strings, but only slightly–it’s something truly weighty through which they press.

Snake-like muscular guitar starts “Everyone Surrounding”, with Michael Robert Hickey’s drums and Tom Farkas’s bass thudding beneath it, while additional guitar draws a web of suspension around that weight. Thanks to a comment from that same Hickey on a video for this very song, I know that the voices are Tyler Klose’s, multi-tracked. If the guitars’ undulations are snake-like, his voice is just riding the waves, until that chorus: “Don’t break down, don’t give it up, you got it/They were wrong about everything you wanted”, where his voice reaches high and chops to a rapid tempo, highlighting the space and lengthy syllables of the line that follows, which emphasizes the song’s title. Indeed, it is that line which finally closes the song, lowering as if defeated to ring for only a moment.

“Aneris” contrasts with the muscle of “Everyone Surrounding” by focusing its introduction on a distinctly picked melodic line. Hickey and Farkas then push the track out of this lazy swing with a thumping beat. The voices in verse are more in line with the feel of the guitars, even when set against that same thumping beat. But when they are kicked into the chorus by a perfect alternation of tom and kick thumps with cymbal and hat work, it hits the kind of chorus that is a lot of what I love about Davenport’s songs: “Talented with bringing the end/Maiden of structure music of minute hand/Broken circles will spin around again”. It’s complemented perfectly by Hickey’s percussive choices and skips along, zigging and zagging up and down in a delightful way. The bridge that follows its second run abandons that for bright, ringing guitar and shorter repetition: “She won’t leave She won’t let you fall/She won’t speak She is above it all”, which takes the instruments back through their first two progressions neatly and catchily, to their end.

Despite the title, “Bulldozer” spends much of its time rather restrained. The opening lacks restraint, in the best possible way: it has a tone that immediately makes me think of Davenport Cabinet as a sound, and, when I first heard it, brought a smile to my face as it confirmed that this was the same band, not a leap entirely away from what had already come. It’s warm and round, akin to a Jeff Lynne sound, though a bit more muted, which is such a wonderful touch that it’s difficult to express how good it just feels. The instruments seem to lead the voices around by their noses, until the words take control: “And never speak my name again to anyone”—the relaxed feel of the song is gone with Hickey pounding away (with a nice touch to the beat that stops it from being simple on-beats) under absolutely electric electric leads. The brakes are put on shortly, though: “And nothing can take you away from me”, returning the song to that tone. When the bridge begins and says, “Will we find a common ground?” I can only respond “Yes,” as the song itself finds a balance between the subdued introduction and the ever-increasing wave that leads to and through the chorus. A brief isolation of muted guitar introduces Scott Styles’s guest solo, which flies off into the stratosphere and perfectly meshes with the return to the tight curls of the chorus’s crescendo which gets one more run through, leaving us with a twinned set of guitar lines.

“In Orbit” lets Hickery veritably paradiddle his way through it, scaling things back and down with that snare focus underpinning a remote slide guitar lead that dips in and out around clean picking that is relatively low in the mix, letting Farkas’s most melodic bass-line drive the song more comfortably. The drums and vocals give the feeling of a sort of impromptu performance of musicians at a porch, or something of that ilk—which is only enhanced by the chorus, which is an excellent example of the harmonized vocals the band favours. It’s a bit of an odd mix: the slide is like something from space, but the rest of the track is utterly earthen. Though the former is not present, the bridge still manages to bring the sounds most completely together, culminating in a sharply toned and soulful lead line that marries the two elements for good.

As if still floating in orbit, slightly reverbed guitar sprinkles out notes in the darkness in “Sorry for Me”, until a lead-in fill from Michael’s drums lights the fuse and the song charges out of the gate. Smooth and slickened slide runs up and down the track’s steady momentum, and then spreads open to a ringing chime—that guitar that was out in space just a few moments earlier. The chorus is falsetto call of the song’s title for normal range answer—“Whenever the captors let me go”—and it actually lets the tempo breathe just a bit. It’s a good thing, as when it comes around again, it’s leading to a winding solo and lead from the guitars that Farkas anchors the hell out of and Hickey creatively backs. A kind of knowing repetition follows the final line, which is indeed heard over and over: “And I’m sorry again”, almost like a broken record, skipping and slowly diminishing to tremolo’d guitar lines that waver out, left to hang as most repeated apologies are. As I played the vinyl version for the first time, I sat hoping, avoiding confirmation, that this would end Side one—not because I wanted it to be over, but because it was the exact right way to end a side. And so I was right—whether by coincidence or agreed plans, I know not.

More coordinates open the second side of the album—“ 74°21’31.7″ W”—and Michael Robert Hickey is left to really shine in his second job: that of string arranger. This time, there is no accompaniment from any rock instruments at all, just a woosh of space and quavering orchestral strings from Jones again, though this intro is yet more brief than the last.

If there was any concern about a relative hesitation to flat out rock on this album, “Students of Disaster” throws it out the window after giving it a good swift kick. Drums crash in and guitars thunder after them, harmonized through melodic leads held to a jolting stop by Farkas’s bass. This time, they don’t really relent for vocals, with even noodling guitar fills sneaking in here or there. While I associate Travis’s voice most strongly with the first time I recall hearing it in isolation—a cover of the Band’s version of “I Shall Be Released”, lending itself more toward folk-rock applications, then—this is where it shines out in its perfect place (recalling somewhat Fire Deuce!). Soaring up to carry the chorus through tinges of the nostalgia that has lingered in all recordings (including the first album, which references it explicitly), it’s almost forgotten when the solo kicks in, book-ended perfectly by runs of that almost operatic chorus. Those big ol’ down-strokes on the chunky riffing just frame the whole thing in great big drapes of rock, which is exactly what it goes out on.

Perhaps to balance out the in-your-face-ness of “Students of Disaster”, the title track that follows is shimmering guitars and even bells, answered by an early Thin Lizzy-esque (we’re talking Vagabonds of the Western World at the latest, and moreso the eponymous debut or Shades of a Blue Orphanage) lead. With phrases like “bag of bones”, “bourbon on my breath” and a title like “Damned Renegades”, there’s a feeling of morose, cowboy campfire tones—enhanced by the Mariachi-like touch of Gabriel Jasmin’s trumpet. The most emphatically instrumental passage of the album is sandwiched in here, with a knotted guitar solo, increasingly plaintive calls from that horn, and stampeding drums—the only voices that follow are non-verbal.

When “Glass Balloon” first started, I thought all the impressions “Renegades” gave me might have been right: a collision of Thin Lizzy’s early sound with a later choice—the sudden up-turn of their “Cowboy Song” to barnstormer. But no, “Glass Balloon” is expertly placed, but independent. Perhaps my favourite of the straight riffs with a nice little hammer-on/off kick to it runs the tune, even when there’s a lead laid over it. Interesting vocal choices mark the brief moments before that riff returns: “But screaming…to fill the void/Speaking to carelessly until I was so ready to go”—that pregnant pause before “to fill the void” is one of those choices that looks weird in words, but sounds strangely right when sung. Hickey’s rampaging snare brings in a new movement: deep, sawing riffs and a trill of distant lead thud and thump up to a four-on-the-floor pounding, which only harmonized guitars can rescue us from the punishment of. A lightly phased refrain of “So ready to go” repeats over that awesome riff, with bending, screeching solo—and suddenly halts.

With that built-in sound of “penultimate track” we come to “Missing Pieces”. Acoustic chords and pointy—I think that’s a 12-string?—electric licks are the fanciest of decorations on the track. It’s more song than showcase, in the least denigrating sense possible. Somber like the title track, but somewhat more hopeful, “Pieces” is a vent for what came just before, not lost for energy, but redirecting it to vocal performance and emoting the core. A quiet passage of bass and guitar marriage helps to enhance the relaxing feel of the song, which shifts the vocals to a distant place in the mix, slowly fading them out with the rest of the track.

“Graves of the Great War” is unquestionably a closer. Timpani rolls in with piano (courtesy of Hickey) and guitar on a slow, steady beat, a kind of dirge, almost. The insistence and power of Klose and Stever is abandoned in vocal, “Aaaahs” chant-like in the background. “We floated your way/There’s not a soul to save/Our journey/Your place” they call out, momentarily re-ignited as if to make the depths of this more clear. And then holy dear lord that guitar. It brings to mind Eddie Hazel, just a bit, to touch on some truly hallowed ground, and it doesn’t overstay its welcome or take it too far. It just spirals out there, emotional fireworks, and then lets the song roll out on its own, strings sweeping in over the beat to find another solo that is just as perfectly controlled and restrained (excellent work, gentlemen!).

—

The most important takeaway I had from this album was its progression from the previous: Nostalgia in Stereo was Travis working out on his own, Our Machine saw the addition of Tyler to give the nascent band an even clearer identity, and now, with the addition of a selected rhythm section (instead of take-what-comes, get-what-you-can as before) really makes itself known. This is the sound of a qualified band this time around. In a year that’s seen the return of Aphex Twin after a decade away, and Braid after even longer, the still-lit spark of a band growing and finding itself, while still retaining enough of its own seeds to be recognizable as progression rather than overhaul shows its worth. Balanced and weighted properly, with care in production, construction, movement, and placement—that’s something not always seen in general, and even less so in this day and age.

I’ve sat here after solid, straight-through listening and then careful dissection (twice, in an even mix of misfortune and fortune—the latter coming from listening again) to find only more to appreciate. This is going to end up somewhere near the top this year, which is no small feat at this point. I would not be surprised if it finally settles into place before all the rest. The way that every instrument, from drum to bass to guitar to vocal serves its purpose and never becomes rote or mechanical, beyond the respects in which a section demands it acquiesce for the “greater good”—an invigorating and heartening thing to hear.

Give the thing a spin, then another, then buy it (I know how you modern audiences work!) and play it some more. I suspect it’s only going to get better—whether “it” is this album, or this band.

¹Apparently, knowing that one “New Post” link fails to trigger auto-saving for a year and a half doesn’t encourage anyone to do anything. Even just remove the bloody link. That will teach me to be used to Blogger’s fully-functional auto-saving…

²”Circle” meaning “Coheed and Cambria”, which is who I was there to see, on a fancy-pants ticket I pre-ordered before becoming unexpectedly unemployed. It turns out I coincidentally share initials with his son! Craziness.